Immigration is often politically toxic. Yet “high-skilled” immigration—the idea of bringing university-educated professionals like doctors and engineers—stands out as a rare point of agreement. I can find no record of a mass protest anywhere in the world against an inflow of skilled foreign workers or against a policy change designed to bring in more of them.

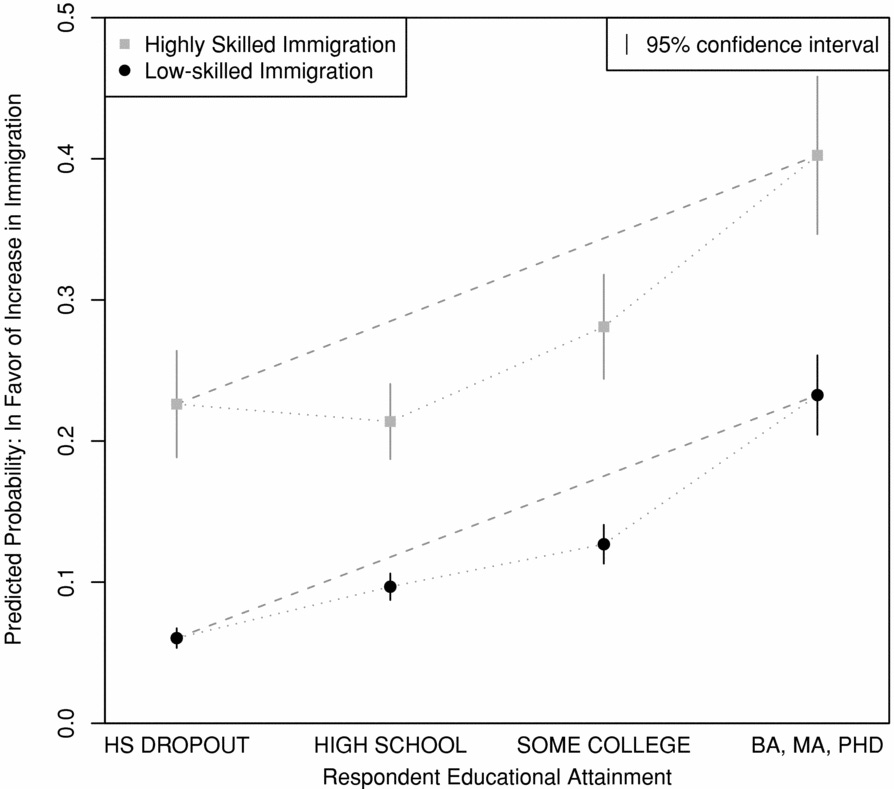

There’s growing recognition across the political spectrum that such skilled migration is both very good for the economy and exceptionally popular. But many smart people still disagree about why it’s popular. The simplest answer, “because it’s good for the economy,” can’t be the whole story since plenty of growth-friendly policies are not popular. And the most common and logical explanation, that “people support it because they don’t personally compete with it,” doesn’t fit the facts either. In reality, the college-educated natives most likely to compete with skilled immigrants are the most supportive.

The real reasons are more interesting, and they also point to how we can make other types of immigration more acceptable, too.

Yes, skilled immigration is extremely popular

I know many people—myself included—who dropped everything else they were working on after coming across Michael Clemens’s famous “Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk” paper showing that removing barriers to migration around the world could deliver economic gains far greater than any other international policy reform. For me, there was a similar lightbulb moment on the political side of the issue when I first saw poll results showing that high-skilled immigration is significantly more popular than any other kind. I saw the same results in my own work and the work of my colleagues, across different contexts, methods, and even in a few real-world policy experiments by governments.

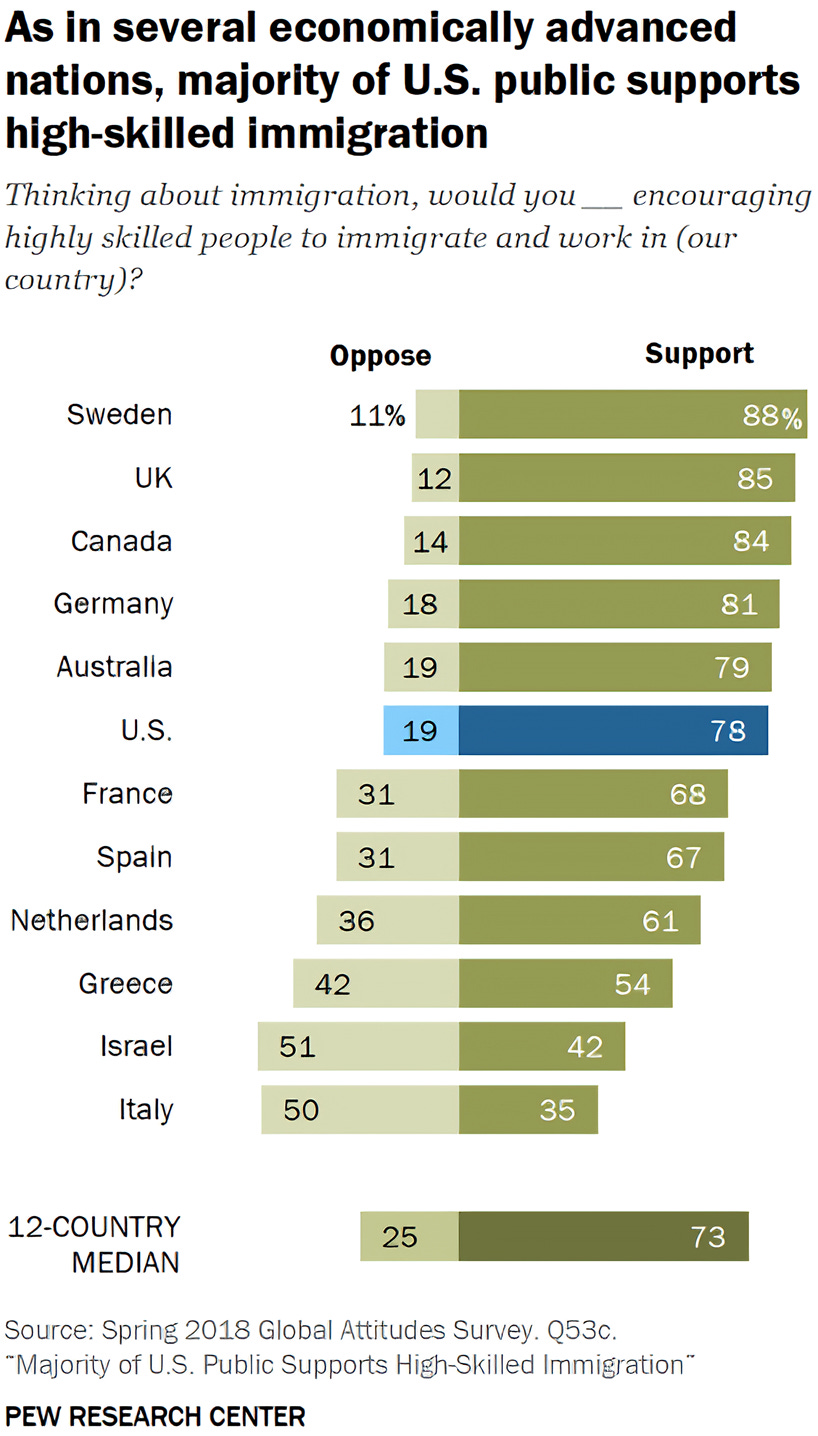

So, let’s be clear about the facts. We know that, in most OECD countries, large pluralities or outright majorities favor admitting more skilled or educated immigrants. In the United States, most major polls usually find a lopsided split in favor of increasing skilled immigration. And the support is remarkably robust, no matter how you ask the question or who you ask: elite or mass publics, left or right, college-educated or not.

It is simply remarkable how robust public support for skilled immigration is. In my recent book, I document that this “skills premium” of people favoring immigration of educated professionals survives every reasonable measurement and analysis choice.

In direct questions about preferred immigration levels or policies, respondents are markedly more positive when the question specifies skilled or highly educated immigrants rather than any other type, or immigration in general.

In conjoint survey experiments where people choose between different otherwise identical immigrant profiles, education and skilled occupation are among the strongest predictors of acceptance across replications.

Support also stays high under all possible clarifications and ways to frame the issue—whether we describe “skills” concretely (engineers, doctors), procedurally (points-based or merit-based), or as a response to specific shortages.

The skills premium also replicates across contexts and subgroups in the U.S., Europe, and other developed and even many developing, immigrant-receiving countries.

And when the immigration debate is more salient or polarized, the relative advantage of skilled work over other categories persists.

And no, it isn’t just about self-interest

The most common explanation prevalent among both academic economists and regular folks is that natives support skilled immigrants simply because they don’t have to compete with them. This explanation makes perfect sense, but the data don’t line up with a simple job-competition account. If self-interest dominated, highly educated natives—those most likely to face competition from skilled immigrants—should be most opposed. In practice, they are most supportive, regardless of their employment status or even political orientation.

But self-interest can matter at the margins and in niche markets. For example, one fascinating targeted survey of tech employees in Silicon Valley showed that these—generally cosmopolitan and pro-immigration—workers were more opposed to expanding the specific (H-1B) visas (which they rightly understood as undermining their job prospects) than the general population. But it is important to keep in mind that such cases are unusual in the mass public, and most voters—not to mention the experts—likely cannot point to a specific visa that would measurably change their personal welfare. I personally, for instance, have no idea how the myriad of Trump’s immigration executive orders would impact my expected employment or income as a professor.

The real reason: intuitive public benefits

If personal job security and class bias aren’t the main drivers, what is? The simplest answer that fits the evidence: natives in receiving states support skilled immigration because they intuitively understand it is good for their country. In academic terms, this support is based on what academics call sociotropic perceptions—judging policies by their impact on “us,” not on one’s paycheck. Regular people may not know or fully understand the enormous benefits of high-skilled immigration for raising productivity and innovation, but they almost instinctively—and quite rightly—see skilled newcomers with a job as a boon for public coffers, able to fill important shortages and revitalize communities.

This isn’t just vibes. In the large conjoint survey experiments of immigrant choice I mentioned earlier, Americans across the political spectrum preferred hypothetical immigrants who had higher education, worked in high-skill jobs, and weren’t expected to need public assistance. They penalized otherwise similar profiles who “lack plans to work” regardless of immigrants’ country of origin. In my research, I also find that even otherwise skeptical respondents are still willing to support policies increasing skilled immigrant workers when these policies are demonstrably beneficial—explicitly and straightforwardly tied to national goals like helping the economy. Finally, in one survey experiment from Japan that I find particularly convincing, respondents stopped supporting hypothetical skilled immigrants when these immigrants were not expected to contribute economically for some reason, whether due to skilled immigrants’ expressed desire to work in low-skilled occupations or not work at all.

More obscure explanations don’t hold up

While few experts believe self-interest matters much in immigration opinion, not everyone agrees with this “sociotropic” interpretation of “skills premium.” Instead, for better or worse, there is still a widespread suspicion among academics that voters may prefer skilled immigrants because of some kind of prejudice, whether it is bias against low-skilled immigrants (which is true almost by definition!) or animus towards specific ethnic groups. In short, the relative popularity of skilled immigration may in part indicate a preference for hierarchy or distaste for people and ethnic groups of lower socio-economic status. I have an old academic paper showing that voters in Spain tend to like immigrants from richer countries, which does not seem to be entirely explained by these immigrants’ economic contributions or cultural closeness. For example, think of British retirees living in Seville who—at least before Brexit—used local services and healthcare for free, didn’t speak the language, yet provoked less backlash from locals than foreign workers from Romania.

But it is important not to miss the forest for the trees. Life is complicated and nuanced, and prejudice is undoubtedly a factor, but the skill premium is so much more than just fancying higher-status foreigners. If a highly educated, white newcomer or group isn’t expected to contribute, support falls just as it does for anyone else. In sum, voters like skilled migrants for what they do, not simply for who they are.

If everyone likes skilled immigrants, why are they restricted?

Given the broad public support and clear advantages of high-skilled immigration, one might assume countries would be racing to admit more of these workers. Skilled immigration can be seen as a prototypical “80/20 issue” that “popularist” pundits and most other political strategists are always searching for. In political science terms, its broad appeal makes it closer to a valence issue than a positional one—where, at least in theory, most voters agree on the goal and would reward politicians who promise, or have a record of, making it happen.

Yet in practice, skilled migration is tightly controlled almost everywhere. Governments impose quotas, bureaucratic hurdles, and narrow eligibility criteria that make moving—even for “best and brightest” talent—quite difficult. There are many possible reasons for this gap between public opinion and policy, from legislative gridlock and polarization to interest group influence. Rather than unpack them all here, I’ll highlight two that are more specific to our current immigration politics.

First, 80/20 support is not 100/0. Even skilled immigration creates winners and losers. And not only in receiving countries but also in sending countries, raising genuine, though not always thought-through, concerns about possible “brain drain.” At the same time, many existing policies, like the U.S. H-1B visa, and even some proposed tweaks, are far from perfect. So, a minority of voters and intellectuals still oppose skilled immigration (and usually all immigration), but they tend to be more vocal and increasingly concentrated on the political right. That concentration can make them disproportionately influential when conservatives are in power. In late 2024, for instance, U.S. Republicans openly split over the H-1B program, with some calling for restrictions and others defending it as vital for growth.

Second, in the United States and many other countries, immigration politics often lumps together everything related to the movement of foreigners: border security, asylum procedures, and the number of skilled-worker visas are treated as parts of the same debate. Politicians worry that being seen as “pro-immigration” in one area could trigger broader backlash, so they hesitate to expand even the most popular programs. This is compounded by the fact that Democrats and other left-wing, pro-immigration parties often prioritize the humanitarian side of immigration over the pragmatic side, leaving skilled migration politically exposed to nativist attacks from the right.

Lessons for why people oppose or might support other types of immigration

Understanding why voters favor skilled migrants offers a simple but powerful lesson: people want to see how newcomers will strengthen their country. Support for skilled migration rests on the perception of clear, tangible national benefits. When immigration is credibly framed as solving urgent problems and filling essential roles, most voters are willing to back it—even if they don’t personally have cosmopolitan values.

This is also why other categories, like lower-skilled migration and humanitarian admissions, tend to face steeper headwinds: their benefits are less immediately visible to the broader public. The challenge is not that such programs can’t bring value (they can!), but that voters struggle to connect them to improvements in their own lives or communities. Bridging that gap means going beyond better messaging by devising better policies that make the contribution concrete and easy to understand by design.

Although some experts are rightly skeptical of immigration bureaucrats’ ability to pinpoint precise up-to-date labor shortages, a promising approach for lower-skilled migration is to tie admissions to the clearest regional or sector-specific long-term needs—such as in childcare, eldercare, and agriculture. For humanitarian migration, private or community sponsorship programs can align new arrivals with the active support of willing locals and businesses, reframing their presence as an asset rather than a burden. In both cases, the goal is to replicate the “win–win” perception that makes skilled migration broadly popular. Over the next weeks, I will be writing about such policies in more detail (stay tuned!).

But the broader point is that immigration need not be a zero-sum battle. Skilled migrants are not popular because voters are blind to competition, but because voters intuit that the country gains from their arrival. Recreating that perception—showing, in concrete terms, how immigration serves the national interest—can expand support well beyond the niche of engineers and scientists. If immigration policy is designed with that in mind, it can become a positive-sum proposition where newcomers are seen not just as people to help or a possible threat, but as friends and partners in building a stronger future for everyone.

If you have too many skilled people for too few jobs requiring the skill, then you can safely expect hostility to highly skilled immigrants of said skill, and a lot of hoops to be jumped for access to employment. Overall though, there are skilled jobs that go unfilled, because natives can be too expensive. For instance, Greek masons were excellent, but too few and expensive, so the influx of skilled Albanian masons was seen very positively. The jobs of Greek masons were enabled and enhanced by the presence of the Albanians. I doubt this would have been the case if Greek masons were too many, and their livelihoods threatened. So it is a game of numbers. Popularity is high when skilled people can be absorbed, but expect it to tank when there are too many.