"Why Don't You House Them Yourself?" — Because I Legally Can't

The political promise and limits of private refugee sponsorship

Despite all its supposed potential, immigration is deeply unpopular today. Refugee and asylum immigration is even more so, because humanitarian appeals don’t resonate much with voters. Most want to see clear benefits for their own country, not just compassion for strangers abroad. That’s why expanding refugee admissions is politically much harder than skilled or labor migration.1

The premise of this newsletter is that making meaningful progress on immigration requires more than just better messaging—it requires better policy. So I wanted to begin with one of the hardest cases and write about a possible solution for making humanitarian immigration more popular and sustainable. What I learned while working on this piece is that one doesn’t have to be a bleeding-heart liberal to support refugees.

Enter programs for private or community sponsorship of refugees for permanent resettlement. The model was first launched in Canada in 1979 and is now being considered or piloted in other countries, including the United States. This policy innovation directly addresses a common skeptical retort in political debates about immigration and humanitarian obligations: “Why don’t you house them yourself?” This question, often used by skeptics to imply hypocrisy among pro-immigration advocates, points to the real and perceived costs of resettlement borne by taxpayers.

But the simple truth is that many people would gladly help refugees with their own money and resources—they just cannot legally do so. Outside of Canada, in most countries around the world—rich or poor, democracies or autocracies—only governments decide who gets to immigrate or resettle there and how, regardless of how generous their populations may be. This issue cuts across ideology—orthodox congregations can’t bring in culturally similar believers, while humanitarians can’t help families in danger even if they want to do it on their own dime.

Community sponsorship aims to change that. It gives willing individuals and private organizations a legal way to act on their motivations to help migrants, share the financial and social costs of resettlement, and show tangible benefits of migration to their communities. Just as importantly, unlike other pro-immigration policies, it creates a durable constituency of both conservative and liberal citizens with a direct stake in immigration and refugee protection. While this is a hard counterfactual to prove, I’m increasingly convinced that had Canada not pioneered sponsorship 45 years ago, it would have resettled far fewer refugees, and its immigration politics would be far more contentious.

There are many good overviews of what community sponsorship is, along with case studies and policy assessments. What I want to do here, in the spirit of Popular by Design’s mission, is something I haven’t seen anyone do yet: assess the potential of sponsorship to generate a more pro-immigration political consensus, both in theory and in practice, and with an open mind for its possible limits. Below, I outline the longest-standing Canadian PSR program, what we can learn from its successes and shortcomings, why it hasn’t spread more widely, the major criticisms, and the available polls on how this idea is received globally. I conclude with a discussion of America’s short-lived Welcome Corps sponsorship program (launched in 2023 but abruptly halted by the second Trump administration), and how better policy design could set it up for greater success if or (hopefully) when it resumes.

What is community sponsorship, and how does it operate?

Community sponsorship is a set of policies that let individuals, community groups, and nonprofit organizations sponsor specific refugees for resettlement in their country, in addition to or otherwise independently of traditional government resettlement. Sponsors cover housing and basic needs, provide social connections, and help with integration, for a defined period, typically twelve months after arrival.

Canada runs the longest-standing and most developed system. Since 1979, hundreds of thousands of regular Canadians have helped resettle around 400,000 privately sponsored refugees with the help of more than 200 local and faith-based groups, all in addition to government-assisted arrivals. In recent years, a slight majority of resettled refugees have come via private sponsorship, and federal targets now plan for more private than government-assisted admissions. Here is the basic breakdown of the current version of Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees (PSR) program:

Who can sponsor: Small groups of five or more Canadian citizens or permanent residents (“G5s”), Community Sponsors (local organizations such as cultural associations, schools, or municipalities), and Sponsorship Agreement Holders (“SAHs”) which are established charities, faith-based communities, or nonprofits previously approved by the government. SAHs also educate and support sponsors and the sponsored, and help resolve issues that arise.

Who can be sponsored: Canadian sponsors may “name” a person abroad who meets Canada’s refugee definition. For sponsorships by G5s or Community Sponsors (but not SAHs), the person must also generally already be recognized as a refugee by UNHCR or a foreign state.2 Because global resettlement slots are scarce (UNHCR projects about 2.5 million refugees in need of resettlement in 2026, a fraction of the 30+ million recognized refugees worldwide), the eligible pool is rather constrained. In practice, the vast majority of named cases are distant relatives or close friends of people in Canada.

What’s required from sponsors: Sponsors commit to 12 months of support: start-up funds, income support, housing, and hands-on help with school, work, and language. Government guidance suggests budgeting about 26,700 CAD for a family of three (minimum, varies by location and in-kind support).

What happens to those sponsored: Resettled refugees arrive as permanent residents, receive federally funded interim health coverage, and after the sponsorship year, can access regular provincial benefits like all other residents.

What the government still does: It sets and manages annual admissions targets (currently 21,000–26,000 for 2025, with new PSR applications paused until December 2025 to reduce backlogs), vets applications, conducts security and medical screening, issues visas and permanent residence, and monitors compliance across all resettlement streams. The federal and provincial governments are responsible for healthcare coverage from the time of arrival and for other benefits that accrue to permanent residents.

The system is now considered a global model that has inspired adaptations in at least 14 other countries while securing financial and other support pledges from dozens of organizations. In 2016, together with UNHCR and a range of non-profit partners, the Government of Canada launched the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative to promote community sponsorship as a complementary pathway for resettlement around the world. Since 2013, Canada has also been running a “mixed” stream, the Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR) program, where sponsors are matched to UNHCR-referred (rather than named) refugees and costs are shared with the government. Many countries have modeled their sponsorship schemes on either this matching approach or the traditional naming approach, with varying parameters.

In Australia, for example, the sponsorship programs can involve business support, but are explicitly counted within the same annual Humanitarian Program quota. In the United States, the Welcome Corps sponsors only provide the first 90 days of core services with arrivals entering as refugees and applying for permanent residency after one year. In Italy, the “Humanitarian Corridors” program allows only organizations (not individuals) to sponsor people on humanitarian visas, so there is no guaranteed permanent residency on arrival.

Why community sponsorship wins more support than resettlement or asylum

Although Canada’s program has occasionally been criticized over sponsor–refugee matching, long wait times, and tension with government quotas, it has not caused any significant right-wing backlash. The same is not true of humanitarian immigration generally—and asylum in particular—which often raises concerns about border chaos, arguably a major driver of recent populist resurgence worldwide. Even in Canada, the right of foreigners to claim asylum at the border is much more controversial than either government-assisted or privately sponsored resettlement or foreign aid.

The political promise of community sponsorship lies exactly in how it channels citizens’ both altruistic and somewhat parochial impulses—helping people you can identify with—into a structured way to resettle vulnerable populations from abroad while maximizing integration success and minimizing the concerns of skeptics. By providing individuals and organizations with a legal and effective way to help, community sponsorship makes larger refugee resettlement more politically durable in otherwise hostile anti-immigration environments.

First, it allows willing citizens to act upon their humanitarian beliefs beyond helping migrants who are already here or voting for a preferred party and leaving refugee protection solely to politicians and bureaucrats. The act of communal sponsorship builds lasting civic networks and constituencies of people invested in resettlement and immigrant success more generally. Research from Canada and other countries shows that sponsors overwhelmingly report positive experiences and stronger ties to their communities.

Second, it appeals to people’s conservative intuitions of localism, faith, and control, especially when “naming” the sponsored refugees is allowed. It is not a coincidence that Canada’s private sponsorship program roots lie in church-based aid and local civic voluntarism. Faith communities were already running settlement ministries and pressing the state to share responsibility, and then stepped in as enthusiastic yet “reluctant partners” during the late-1970s resettlement of Southeast Asian refugees. According to a recent survey of sponsorship organizations in Canada, 60% of them still belong to a religious organization, while 22% focus on another particular non-religious ethnic community or group.

Third, community sponsorship explicitly addresses common public fears. Because sponsors shoulder much of the cost and responsibility, perceived fiscal burdens are lower. Because sponsorship groups tend to be deeply involved in helping refugees they sponsor—finding housing, connecting newcomers to schools and jobs—social cohesion and integration outcomes should be stronger. While no randomized trials exist, observational studies generally find better integration outcomes in employment and income for privately sponsored individuals compared to government-assisted refugees, which is only partly explained by selection bias. A recent study by the Canadian government found that after one year 75% of privately sponsored refugees had employment earnings vs 37% of government-assisted, and social assistance receipt was 16% vs 93%, with advantages persisting over several years.

To my surprise, however, despite nearly half a century of Canada’s private sponsorship program and its recent global proliferation, direct public opinion evidence on the topic is scant. The only report I was able to find on public attitudes and sponsorship found high support but mostly relied on indirect or qualitative evidence (e.g., more positive general immigration attitudes among people who have participated or live in high-sponsorship areas). After further investigation, which took me much longer than I care to admit, I was able to locate a few relevant surveys that straightforwardly ask people about their support for sponsorship programs.

Here are the key reports and their highlights:

In Canada, a vast majority are aware of the private resettlement program (which is impressive given the generally low political knowledge in public opinion). A clear majority—especially those who are aware—view it favorably. According to the 2018 and 2021 Environics surveys, about 3-7% say they have been directly involved, 15–25% say they personally know a sponsor, and about the same share say they would like to participate in the future. A 2017 McGill survey, which explicitly asked whether private sponsorship or government resettlement works better, found that significantly more respondents chose the former (41% vs. 6%, with the rest unsure).

A 2021 Environics poll found that, among the small minority who view private sponsorship negatively (13-16%), reasons cluster around how the program is administered (taxpayer burden, insufficient resources) or unfavorable views of refugees (concerns about integration or competition for resources). Although these skeptics were not asked about other policies, it is reasonable to assume they have similar or stronger concerns about traditional government resettlement.

In Germany, a 2016 More in Common survey conducted during the Syrian crisis found 45% in favor of introducing a sponsorship program, with about one-third opposed. These levels exceeded general positivity toward “refugees” at the time. Forty percent also reported donating or volunteering to help refugees, and 22% said they would be willing to participate in a sponsorship program.

In the United Kingdom, a 2021 More in Common survey found 48% support and 34% opposition to accepting more (Afghan) refugees via community sponsorship. Net support was 14 points higher than for general resettlement, driven mainly by lower opposition among socially conservative and anti-immigration segments of the population.

In Poland, a 2024 CMR Ipsos survey found 31-39% support for introducing a sponsorship program—the only case I saw where opposition exceeded support somewhat. Even so, community sponsorship was more popular than traditional government-led resettlement. An earlier survey from May 2022, fielded shortly after the start of the war in Ukraine by the same research team, reported much higher support numbers.

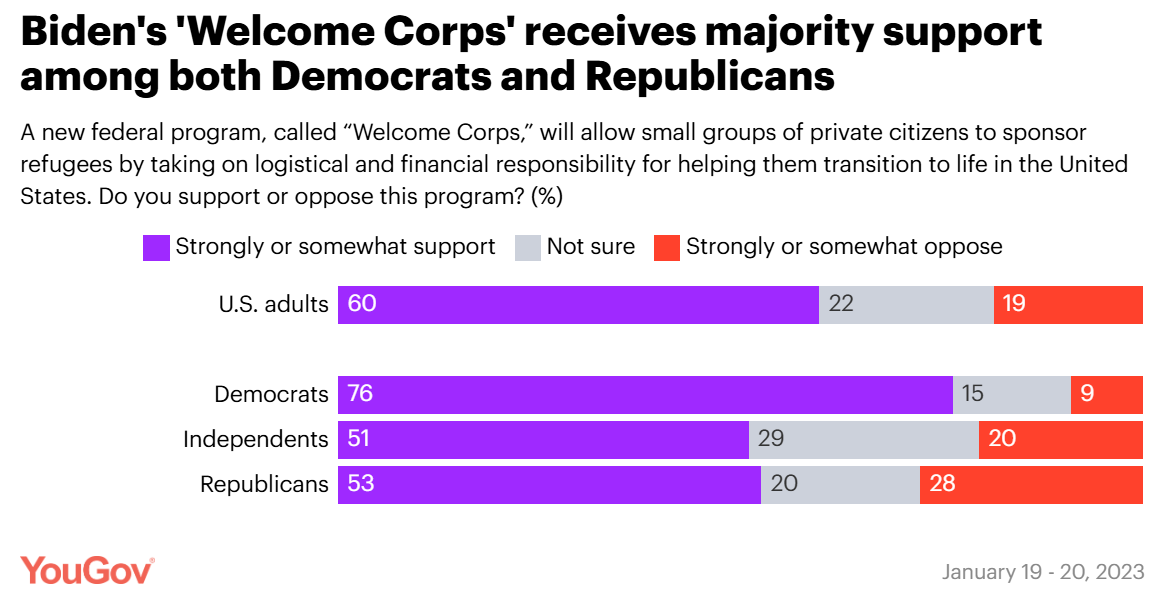

In the United States, a 2023 YouGov survey at the launch of Welcome Corps showed 60% overall support, including 76% of Democrats and 53% of Republicans. Given heightened border salience and a thermostatic cooling on immigration during the Biden administration, these are notable figures. About one in four Americans also expressed interest in personally sponsoring a refugee in the coming years.

Bottom line: Community sponsorship is broadly popular—either absolute majorities or strong pluralities support it across various contexts—and it tends to outscore government-only resettlement and many other humanitarian policies.

Why hasn’t it caught on more? The major bottlenecks and limits of sponsorship

If community sponsorship works so well, why hasn’t it spread more widely? Despite my constant reminder to immigration advocates that humanitarian intentions are rarer than they assume, my sense is that the answer is probably not a lack of willing citizens. The Canadian surveys I described earlier show that a small but meaningful share of the public already participated (about 3-7%), or would like to participate (another 5–15%) if given the chance. This aligns well with my own surveys and incentivized experiments: while most people understandably prioritize their own or their country’s well-being, at least 10% in rich democracies display pronounced humanitarian motivations and are willing to benefit foreigners even at a personal cost. Even if we take a very conservative cap of 5% of the working-age population as the potential pool of sponsors, that is still a large number. Extrapolated to the United States and other rich democracies, this implies millions of potential sponsors. In short, public enthusiasm seems sufficient.

The bottleneck is the government’s resolve and capacity. Policy innovation in immigration is slow, especially when leaders want clear proof of success before scaling. Even Canada’s famous points-based skilled migration system took years to become a global practice. And sponsorship requires more than goodwill—it demands real administrative capacity.

Governments must vet sponsors, screen refugees, issue visas, arrange travel, monitor cases, and step in if failures occur. Many countries lack the bureaucratic infrastructure or trust in civil society to manage this. The start-up costs of building sponsor networks, training groups, and supporting them through the process are significant. Philanthropic seed funding has increased recently but remains modest, and officials rarely see enough upside to overcome inertia.

Even if some of these bottlenecks ease, community sponsorship is clearly not going to solve the world’s displacement crises alone. There are over 35 million refugees worldwide, with 2–3 million designated as urgent resettlement cases, and each year, only a fraction are resettled anywhere. If every wealthy nation decided to adopt the Canadian sponsorship model tomorrow, total numbers would still be in the hundreds of thousands per year, not millions.

Moreover, community sponsorship does not address the messy, politically toxic issue of spontaneous border crossings and asylum claims. Sponsorship is simply not designed for these scenarios—it is orderly and selective, which is the opposite of chaotic inflows. Some development economists—and now even The Economist—argue the asylum system is outdated and should be rebuilt around protection and legal work in proximate host countries, fewer camps, and more legal pathways with regional processing to deter dangerous journeys. In that reimagined setup, community sponsorship could serve as one of the channels to redirect some of the would-be asylum seekers into managed programs supported by citizens. But realizing this would require policy shifts far beyond sponsorship itself.

Interlude: the successful, yet short-lived, case of U.S. Welcome Corps

The recent two-year U.S. sponsorship experience illustrates both the appeal and fragility of sponsorship. The Welcome Corps, launched in 2023 as a pilot within the federal refugee admissions program, invited Americans to form groups and directly sponsor refugees for the first time. Several observers even called it a “revolution” in the U.S. refugee admissions or even immigration policy in general. The response was remarkable: more than 160,000 people across every state registered interest within two years. The most engaged states ranged from Minnesota and California to Texas and Indiana, showing geographic and political diversity.

Public opinion matched this enthusiasm. A YouGov poll found 60% of Americans supported the idea, including 76% of Democrats and 53% of Republicans. For a pro-immigration policy initiated by a Democratic administration to secure majority Republican support in 2023 was striking.

At the same time, the program did not generate any evident backlash. Some anti-immigration groups raised alarms about potential fraud and weaker vetting (which they do about pretty much all immigration programs), but a review by the Niskanen Center found those concerns unsubstantiated. Refugees underwent the same security screening as in other resettlement channels, and sponsors themselves were background-checked and trained. No major scandals occurred: refugees were vetted, sponsors were supported by intermediary nonprofits, and cases proceeded smoothly.

The U.S. case demonstrates the political potential of sponsorship: grassroots enthusiasm, broad partisan reach, and no visible backlash. It is not proof of long-term success, but it shows how strongly the model resonates with American civic culture. The Welcome Corps ended only because refugee admissions overall were paused by the second Trump administration in early 2025—not because of any explicit opposition to the program itself. If and when revived, it would likely continue to draw bipartisan interest.

Learning from Canada, the U.S. pilot, and other countries, we can try to identify some key design principles that make a community sponsorship program both more sustainable and scalable, from rigorous participant vetting to well-funded administration. I will write about these, as well as possible extensions to the program, in a separate post in the future. For now, I want to highlight two features that I find especially important for the program’s political success (notably absent in the initial version of the U.S. Welcome Corps program): naming and additionality.

Naming and additionality: the key sponsorship principles and the debates around them

As with any reasonable policy compromise, community sponsorship programs and their key principles have also been debated and criticized on both the left and the right. Let’s start with the aforementioned naming principle, which essentially allows sponsors in Canada to pick specific refugees (at least among those who qualify for resettlement by law). This principle raises obvious fairness questions: Are those refugees the neediest, or just the best connected? These concerns have led some left-leaning analysts to criticize the naming feature of private sponsorship as inequitable, since it tends to prioritize refugees who have family or friends abroad.

Although I have found relatively little explicit criticism from the Canadian right focused on the program itself, the concerns I did find are almost a mirror image. In particular, some worry that private sponsorship could become a sneaky backdoor for increasing lower-skilled immigration, in relative or absolute terms. Because sponsors usually name their relatives or co-ethnic friends, the program might be used to bring in people who would not qualify under stricter points-based streams. The most troubling aspect for these critics is that sponsorship leads to permanent resettlement, meaning those brought in—and their descendants—may draw on taxpayer-funded benefits if they contribute less in taxes than they consume. Given Sweden’s disappointing experience in improving fiscal outcomes for humanitarian migrants and their families despite strong integration efforts, this critique should not be easily dismissed.

As some rightly argue, however, one of the Canadian program’s strengths compared to its many offshoots is precisely that sponsors are allowed (though not required) to nominate specific refugees. Equity and human capital concerns aside, naming taps into the strongest motivations people have to sponsor in the first place. Individuals and groups are more committed when the person they welcome is not a stranger, but someone they already know, or someone with whom they feel a direct cultural or religious connection. Prior relationships often bring shared language and customs, which can ease integration. Besides, sponsors can also nominate people they do not already know, enabling creative uses such as campus sponsorship for refugee students or partnerships focused on sexual and gender minority refugees.

At the same time, matching-only streams like the aforementioned BVOR program have struggled to mobilize and retain large numbers of sponsors. After completing a matched case, many groups end up seeking channels that let them name specific people to help their relatives or friends. The U.S. Welcome Corps, for example, saw faster uptake after adding a possibility for naming in the second phase of the program, underscoring how the ability to nominate specific people can drive participation. In short, naming makes the program work politically by sustaining civic engagement over decades, even if it may complicate the purist ideals of impartial humanitarian protection or skill selection.

But the most serious structural critique of the program relates to the additionality principle or the lack thereof. Does sponsorship actually increase protection for vulnerable people, or does it substitute for government action? In 1979, when the program started during the Indochinese resettlement, the federal government made an explicit one-for-one pledge (one government-assisted admission for each privately sponsored case). The pledge was discontinued soon after as backlogs grew. Today, the government sets separate targets for government-assisted and privately sponsored streams, and allocations can shift between them from year to year.

This raises the familiar “crowd-out” concern: if volunteers sponsor 10,000 refugees, a cost-conscious government might reduce its own intake by a similar amount, yielding no net increase. The risk is debated and hard to prove, but in some years PSR admissions have exceeded GARs, which sponsors cited as contradicting their additionality expectations—even though additionality is not part of the PSR official program theory anymore.

From a political perspective, however, even a pure substitution arguably can have an upside: if taxpayers see that enthusiastic citizens are handling more refugees, it might reduce backlash and keep overall support higher than if the government tried to do it all. It also effectively addresses the most salient conservative critiques of the program. Still, for community sponsorship to reach its full potential, it ideally needs to complement, even imperfectly, not fully supplement, government resettlement.

Clear government commitments can prevent this—whether through pledges that private sponsorship will not reduce overall quotas, or even through formulas that increase official resettlement proportionally. Transparency is also essential: if citizens can see that their efforts genuinely expand the total number of refugees welcomed, more will step up. Creative mechanisms could reinforce this link, such as tying sponsor contributions directly to funding additional government-assisted arrivals. However it is achieved, additionality, even when it is only partial, is the key to unlocking sponsorship’s promise: mobilizing private compassion to help vulnerable populations beyond voting or charitable donations.

So, how can sponsorship make our immigration politics better?

Despite current challenges and limits, I believe that community sponsorship of refugees has a bright future. Its track record in Canada shows it can make refugee resettlement more popular and politically sustainable, even where traditional humanitarian policies face hostility. Programs that empower citizens to welcome refugees consistently score higher approval than almost any other immigration initiative. They harness grassroots goodwill that would otherwise go untapped. And they tangibly benefit not only refugees, who get a chance at a new life in a supportive environment, but also hosts, who often find new purpose and social ties, and their communities, which gain integrated workers amid population decline.

In an age of polarized politics, community sponsorship uniquely appeals to a broad demographic and manages to bring unlikely allies together—church groups and LGBT nonprofits, veteran groups and humanitarian agencies, liberals and conservatives, small towns and big cities. This coalition-building effect is invaluable for the long-term sustainability of refugee protection. It is much harder to demonize “refugees” in the abstract when your neighbors, co-workers, or your parents’ church are personally helping someone settle nearby.

In the more immediate future, we are likely to see continued scaling up country by country. The new Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative has been advising governments, and roughly 14 countries have launched some version since 2016. Most remain pilot-sized and have resettled only a few thousand families, though separate family-reunion pathways for Ukrainians brought in tens of thousands under a similar sponsorship principle.

The real game-changer would be the U.S. fully embracing community sponsorship with naming alongside its government program. If the U.S. activated hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of willing sponsors, or even reached Canadian-level per capita rates, we could be talking about hundreds of thousands of refugees resettled annually via private means. Even if those numbers are aspirational, they illustrate significant untapped capacity. High-income countries collectively host only a small fraction of the world’s refugees today, but by empowering their own citizens to sponsor refugees, they could increase that share in a politically sustainable way.

Community sponsorship will not solve the refugee crisis on its own, and it will not replace the need for robust government action and international cooperation. But it will give tens of thousands of people a safe new home who would not have had one otherwise. In a world where so much of the immigration debate is abstract and mistrustful, community sponsorship offers a concrete and intuitively positive story: regular people working together on something compassionate and constructive, with visible results that many can admire even if they choose not to participate. That is a useful antidote to cynicism and a reason to think that, while community sponsorship may not transform global numbers overnight, it can improve our immigration politics over the long run, making it more open and humane by design.

Many thanks to Gabriella D’Avino, Ania Kwadrans, Biftu Yousuf, and BBI fellows for their help and comments on this piece.

Select bibliography

Fratzke, S., Kainz, L., Beirens, H., Dorst, E., & Bolter, J. (2019). Refugee sponsorship programmes: A global state of play and opportunities for investment. Migration Policy Institute.

Labman, S., & Cameron, G. (Eds.). (2020). Strangers to neighbours: Refugee sponsorship in context (Vol. 3). McGill-Queen’s Press.

Cameron, G. (2021). Send them here: Religion, politics, and refugee resettlement in North America (Vol. 5). McGill-Queen’s Press.

Kaida, L., Hou, F., & Stick, M. (2020). The long-term economic integration of resettled refugees in Canada: A comparison of privately sponsored refugees and government-assisted refugees. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(9), 1687-1708.

Labman, S. (2016). Private sponsorship: Complementary or conflicting interests?. Refuge, 32, 67.

Manks, M., Monsef, M., & Wagner, D. (2022). Sponsorship in the Context of Complementary Pathways. Knowledge Briefs.

Sustainable Practices of Integration (SPRING) podcast about Canada’s sponsorship.

Private Refugee Sponsorship in Canada - 2021 Market Study, Environics Institute.

Orth, T. (2023). Most Americans support “Welcome Corps,” Biden’s new refugee sponsorship program. YouGov.

I should note that while much evidence shows humanitarian immigration is unpopular, some researchers and advocates present contrary findings. I’ll examine that contradictory evidence in detail in my future posts.

To accommodate surges in sponsorship during specific crises, the government has occasionally waived this recognition requirement (e.g., for many Syrian cases in 2015–2017).